Introduction

“A people which takes no pride in the noble achievements of remote ancestors whill [an old-fashioned version of ‘will’] never achieve anything worthy to be remembered with pride by remote descendants.”—Lord McCauley, from Grandmommy’s book titled Genealogy

The following story is about my family.

I would not be telling it to you if not for a violent end. Without extreme emotion, often graphic violence, it is hard to get our attention. I am just like everyone else in this regard.

We care. It’s just that there is so much to think about today. We don’t have enough emotional bandwidth to pay attention in our distracted lives. If it doesn’t “bleed,” as they say, it isn’t going to “lead” on our social media, news sites, or even in an old-fashioned newspaper. Well, this story does bleed, even if slowly.

It is told from the perspective of one man trying to understand himself and his family in the third decade of the twenty-first century. This family is representative of many American families. It has claimed wonderful patriots and entrepreneurs, good citizens, and good Christians. But it has also spoken words and performed deeds that are surely racist, sexist, and non-gender-affirming. It has not been a perfect family by any means.

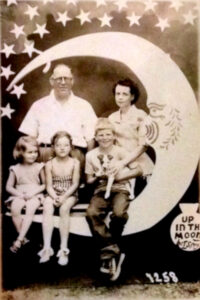

Grandmommy told me just weeks before she died that I would be my generation’s genealogist. She had compiled a skillfully-typed history on onion skin paper. It detailed who-begat-who, when they moved from Wales and England to the British Colonies, and where they lived in what would become the Southern United States.

This story is not at all like that. It dwells on the events and the experiences that shed light upon our big American family today. In a way it is an homage to the good of everyone’s brother or sister. But it is much more a sincere prayer that we all can embrace the varied stories of our many families, our friends, and our communities.

In a world that cannot agree upon facts or abide theories, bridging the chasms separating us all depends upon listening to one another’s stories, recognizing our faults, accepting our differences, and discovering our many shared virtues. As a younger person I would scoff at the use of the word “love,” but we will likely need some of that, too.

If we can do these things, we might just be able to make it through America’s Culture War together.

Foundational Years

“They are, in effect, still trapped in a history which

they do not understand…”

—James Baldwin, The Fire Next Time, 1963

1: America’s Culture War

I grew up in the South with a father who believed that we Americans were fighting a culture war amongst ourselves, an ongoing civil war. Dad saw active battles in the schools, in the churches, in the news media, in our businesses, and certainly in politics. To him, they were over the fair treatment of people and the fair allocation of resources.

Someone reading that last sentence in 2020 might think my Dad a social justice warrior. He certainly was a rebel. It took me years to understand how very different each person’s ideas of fairness can be.

Dad was most focused on the unfair treatment of his fellow Southerners. He believed the federal government in Washington, D.C. just couldn’t stop taking away rights. Mom was more interested in the broader assault on the individual. If only society could keep its hands off, each person could achieve great things.

My sister, brother, and I quickly came to understand how different our world was from the one our parents had grown up in. During our early childhoods, we saw AT&T’s rotary phone replaced by a touch-tone device. Despite that advancement, almost every time we called Grandma in Lake Wales, Florida, we had to wait on her party line, a phone line shared with other families.

It was not uncommon to hear a foreign voice jump into our conversation. Grandma would patiently respond to that voice, “Lilly, these are my grandchildren from Memphis. Can I speak with them for ten more minutes?” I’d hazard a guess that Lilly, Greg, Edith, Matthew, Mary Lou, Ezekiel, and their children knew more about one another’s real lives than a lot of Facebook friends do today. I suspect it brought them all together in some ways.

Grandma always said goodbye to us by announcing, “I know this long-distance call is costing you a ton of money. I better get off now. Love you!” Connecting in those times could be expensive, but it meant a lot to family and friends.

As a young adult I came to think my Dad wrong about most things. He clearly did not bridge the gap very well with people he saw as different. The three of us kids worked to span those gaps in college and mid-life. Over more recent years, though, I have come to understand some of Dad’s assertions a lot better, things my elite college education had pushed me away from.

I like to imagine I’m a lot more balanced today than I was during any of my school years. I’m comfortable with a middle ground and willing to try different tactics to see what works in the real world.

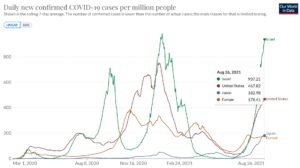

Realistically, though, there may be only one thing I agree completely with the Dad I knew as a child: America is fighting a culture war. Covid-19 and the killing of George Floyd have shown us how people won’t just try to solve problems. Instead they’d rather fight about the philosophies behind the solutions. Before we take care of people, we have to argue over the politics. This American Culture War has seeped into almost everything we do and all of our organizations, even the ways we interact with friends.

The tricky thing about wars is that they cloud our judgement and blur our values. Yes, war can bring out the best in people. But more often war brings out the worst. We begin acting as if the outcome will determine the very life or death of those we love the most.

Quite true.

2: So Much In A Name

My brother, JT, was named after a great-great grandfather on my Mom’s side, John Thomas Trenton. The Trentons did not believe in using the same name successively. There were no juniors or III’s or IV’s. The family names were never allowed to wander too far away, however. They all had a deeper meaning that tied each one of us to our ancestors, to their stories, and to the places they came from.

Things were a little different in parts of Dad’s family. You had to be careful in reunions. If you said the name “Stewart” too loudly, a whole room of men would turn their heads. There would come an important moment in life when an adult cousin would correct you, “No, I don’t go by Stew anymore. Stew is my son. I go by ‘Stewart,’ same as Dad now.” It could get confusing.

It took me a while to learn my Mom and Dad’s given names. They were “Mom” and “Dad” for years, simple titles but extremely powerful. Only ever replaced by a “Ma’am” or “Sir” delivered respectfully. Understanding my father as a person did not begin until I started reading the names on our mail. It was shocking to learn that there were so many different men receiving letters in our home. I became sincerely frightened that something was extremely wrong.

My Dad’s first and middle names were “James” and “Earle.” The birth certificate did not matter much, though, because his family never called him anything other than “Johnny” or “John.” Those were the names I came to know him by. The name, Johnny, however, didn’t link directly to any ancestor I ever remember meeting or hearing about.

I was eventually told that on the day he was born in 1939, a grandfather declared that he would be called Johnny, no matter what. Recently I connected the dots. The name “Johnny” was used to describe the common soldier of the Confederacy. Since the Civil War, the name is found in books, songs, games, and what today we call cultural memes.

A memorable incarnation is the 30-inch “Johnny Reb” toy cannon of 1961. Remco capitalized on the 100-year anniversary of the Civil War. It packaged a working cannon with a rebel battle flag and four solid balls. Properly fired, a shot could travel up to 35 feet.

On April 4, 1968, less than two weeks after I was born in Memphis, Tennessee, my father’s birth name was in the news. Mom received a rare call from her mother-in-law. Grandma immediately asked in her quiet, breathy voice, “Is Johnny around?”

Grandma had heard a radio announcement that Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. had been assassinated that very morning with a rifle used by a White man in downtown Memphis, our home town. The FBI had released only the first and middle names of the shooter: James Earl.

Mom responded, “Well, yes. I think he’s in the backyard.”

Grandma asked for further clarification: “Has he been around all day?”

Grandma knew she had a loving and dutiful son raised in a Christian home. Yet she was terrified by the news of MLK’s killing in Memphis. Her son, my father, was quick to anger. He bore a deep resentment for what he saw as injustices being thrust upon his home by the US court system and the federal Presidency. He was also a good shot after years in the army. Grandma, a deeply loving and Christian woman, feared that her son with the electric smile might have done the unthinkable.

3: Foundational Memories

Most of us grow up with stories about ourselves as young children. Some are of events so early in life that they are unlikely to be truly remembered. Nonetheless, these stories become foundational memories because we hear them told so often and so vividly.

JT, my little brother, always heard the tale of his birth: “You were so small when you came out of your Momma, I could hold you in one hand. Like a floppy little bird!”

He was born extremely premature. Mom told us the doctors said he was sure to die. The hospital had never seen such a preemie survive before.

My first foundational memory is of me and the geese. I was barely walking, just over a year old. Mom and Dad were still young and beautiful and having fun together. Our threesome was sitting next to a pond where I spotted a gaggle of geese. I toddled over and began chasing them with the joy inspired by newfound mobility. Once the geese understood the weakness of the attack upon them, they, like any self-respecting group, turned the tables and started chasing me. My giddy joy transformed into terror.

When Mom tells the story, even today, she emphasizes how funny it was, watching me waddling away as fast as I could, pursued by giant birds. Dad would rise to the moment and declare, “Do you know what those geese would do to a baby? If I hadn’t run to catch him up, they would have killed him!” Dad saw and feared the hurtful nature of groups far more than Mom.

Mom’s style was quite her own. I wondered if it was because she grew up dearly loving her older brother. Stan was born deaf. When you watched Mom talk with him, you saw her sit close. To get his attention she would grab his shoulder or tug on his shirt. She would make certain he could see her lips move with explicit precision. Sometimes she spoke in normal tones, sometimes without much sound at all, and sometimes like she was yelling across a field.

Mom’s sense of humor was larger than life. The jokes she told were tailored to multiple audience types, those that were hearing and those that were deaf. She kept the gestures big and the punch-lines accentuated.

Mom found the occasional practical joke horribly funny, too. I loved milk and would gulp it down at dinner. One hot, summer night, she had prepared a great trick. Knowing that buttermilk is closer in taste to vinegar than to butter or milk, she had poured buttermilk into my glass. The plot played out perfectly when I took a big gulp and then spit the buttermilk involuntarily all over JT. The mess over our half of the table was disastrous, but she laughed joyfully as she cleaned it up.

It was not so hilarious for my brother or me. And it would not be the last time I had to carefully clean his face and neck.